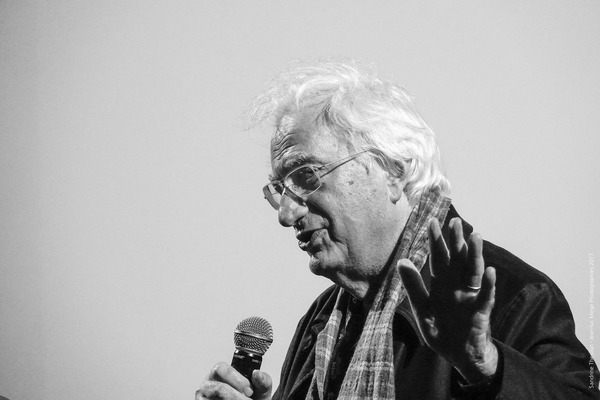

BERTRAND TAVERNIER

charters new Journeys Through French Cinema

TUESDAY, OCTOBER 17, 2017

"We must fight the idea that the only interesting films are those that have just been released." Among the rare moments offered to the public this edition, an exclusive premiere of My Voyages through French Cinema, a passionately personal endeavor: eight episodes (totaling seven and a half hours) of French cinema from the 1930s to 1970s, by Bertrand Tavernier. An interview with the filmmaker, also President of the Institut Lumière.

© Institut Lumière / Sandrine Thésillat

Festivalgoers may have already seen his previous documentary, My Journey Through French Cinema. Released last year and screened at Sundance, Cannes (Cannes Classics), Telluride, New York and San Sebastián, it was screened at Lumière in 2016. This time around, Lumière audiences will be the only ones to discover the series on the big screen – an odyssey in eight chapters – before the series moves to television for broadcast on Ciné+ and then France 5. This "wandering" journey takes us to on a trip to Bertrand Tavernier’s “nightstand” filmmakers (two episodes), continues on with songs, Julien Duvivier, the cinema under the Occupation (pre and post-war), unknown directors, and the 1960s. This work of "transmission” is also undertaken by other directors such as “Martin Scorsese, Quentin Tarantino, Alexander Payne and Joe Dante in the United States, and by actors like Vincent Lindon in France,” he says. "We must not be nostalgic, we must be open and interested in what is happening in the present," says Bertrand Tavernier, who is just coming out of the screening of The Shape of Water, the latest film by Mexican Guillermo del Toro, a film the former describes as "astounding."

"But we must also fight the idea that the only interesting works are those that have just been released," he continues. "The previous filmmakers paved the way: if I’ve been able to make my films with real freedom, I owe it to all the great battles that people like Julien Duvivier, Claude Autant-Lara, Jacques Becker or Jean Grémillon waged against financiers, against censorship. We must know how to express our gratitude," says the filmmaker, always happy to pay tribute to those who have forged his cinephilia. On television, Arte "does a magnificent job", but "there is a sort of panic, vis-à-vis heritage films and black and white flicks, as if they are a contagious disease,” he laments. Moreover, among “all the French films listed by the CNC, less than a third of them are available (all formats combined), under legal conditions, at decent prices, despite the laudable effort made by Gaumont and Pathé” to safeguard their heritage.

It was not possible for the series to pay tribute to the work of certain filmmakers, "because nothing was digitized. There are 35 mm prints that exist at the Film Archives, but when no work has been done on them, using a clip is extremely expensive," explains Bertrand Tavernier. If the works of famous filmmakers such as Jacques Becker, Jean-Pierre Melville and Jean Renoir are now accessible, the films of other directors remain impossible because they have not been restored. The film My Journey Through French Cinema has helped "a good number of films" to be restored "and the series will help them" also, reports the filmmaker. "A guy like André Berthomieu, it seems that two or three of his films still exist but it’s impossible to find them! Some films by Jean Boyer also seem hopelessly lost.”

The filmmaker, however, helped bring back Remous (1934) by Gréville, which "had not been available for 30 years. It did not even exist on VHS". More recent, yet "impossible to obtain, despite being his press attaché," he recalls, are Claude Chabrol's films such as Le Boucher (1970) or This Man Must Die (1969). The same goes for Time to Live (1969) by Bernard Paul, Pierre and Paul (1969) by René Allio, Voyage of Silence (1967) by Christian de Chalonge "screened at the Institut Lumière," or Law of Survival (1967), the "first film by José Giovanni, with Lino Ventura: impossible to find!" he exclaims with regret. "When, by chance, people from Pathé, Gaumont, TF1 or M6 manage to get their hands on them, they are suddenly restored are rereleased...". But "there are missing films, because the material is lacking," especially in the 60s and early 70s. "It's almost easier to see films from the 1930s, because our initial efforts focused on this period, when so many films were missing..."

Rébecca Frasquet