We head west once again!

THURSDAY, OCTOBER 18, 2017

Those who say the western is a genre for little kids who played cowboys ‘n’ Indians long ago, are wrong. Because nothing is more modern than Classic Westerns, a wonderful series of an eternal cinematographic genre.

Beyond the legendary movies to discover or to see again –The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) or My Darling Clementine (1946), where, more than ever, John Ford demonstrates that you don’t need rules to get it right, or Red River by Howard Hawks, (1948), Shane by George Stevens (1953), or High Noon by Fred Zinnemann (1952) - Bertrand Tavernier, the driving force behind the genre series, has also chosen lesser-known, but impactful westerns.

The right to hang around town

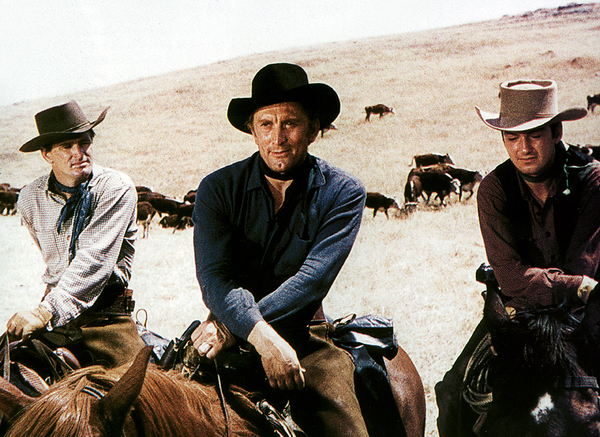

The western means living free in America – it is a fleeting postulate easier to dream about than to apply. The necessity to keep on moving amidst dangers haunts Man without a Star, (King Vidor, 1955). From the first minutes, Vidor gives his hero, Kirk Douglas (in venetian-blond, tough-guy mode), the bright idea of traveling clandestinely by train in the wildness of Wyoming, where one kills, no questions asked. A weapon-less cowboy, Douglas longs for the fulfilling life in the great outdoors, in the west, where one must take it all in… and leave quickly.

Human consciousness and little bastards

Devil's Doorway (Anthony Mann, 1950), Broken Arrow (Delmer Daves, 1950) or Gunman's Walk (Phil Karlson, 1958), less libertarian but great films of the subversive left; deal with miscegenation, violent coexistence between communities (here Indian and white), and consequently of the notion of legacy, utterly relevant in today’s America, ever in danger of cannibalizing itself. The Ox-Bow Incident (William Wellman, 1943) is therefore imperative to discover. This powerful film is carried by the sweetness of a Henry Fonda in over his head, frightened in the face of the powerful hate in the name of a sacrosanct property. A good strategist, Wellman takes the audience step by step toward the horror of an unbalanced confrontation between two groups of men. It goes so far that it is hard to believe. The end, involving a certain letter, is unforgettable.

Great feminists and more

Rarely has a genre, particularly one known for its manly characters, given women such awesome roles. Diane Varsi and Janet Leigh, dressed for the rough outdoors, face dangers in From Hell to Texas (Henry Hathaway, 1958) and The Naked Spur (Anthony Mann, 1953), respectively... In Day of the Outlaw (André De Toth, 1959), women hold the promise of an Eden, to be attained at any cost, even if it means coercion without understanding, like with the strange ball scene. In the film, a nearly abstract western, where one dies in the snow, men, lost in the vague landscape, see their relationship with women as the only thing worth living for. What is intriguing, is that De Toth unfolds his narrative, not with a sense of romanticism, but rather, with an unexpectedly beautiful bleakness… However, the most fascinating movie of all, with its scene where the man forces the girl to dance, is Pursued (Raoul Walsch 1947). Rarely a movie, let alone a Western, has managed to film the exact level and difference in temperament between the masculine and the feminine, with the aim of bringing them together better. Robert Mitchum, displaying physical and moral strength, awaits the vibrant Teresa Wright. The two of them in close quarters are perpetually on the verge of a violence, so they attempt to substitute trust by love. The western, in all this, reminds the world that wild west is never far away. At the heart of this universe, losing all sense of orientation is possible!

Virginie Apiou

> Genre Series: Classic westerns by Bertrand Tavernier